Our chief economics and international affairs adviser Gail Soutar reports.

The Trade Policy Dilema

Following a BREXIT the UK government would have to decide how to fill the “policy vacuum” in the areas where the EU currently has competence. It would also have to negotiate the kind of trade relationships it wanted with the EU27 and the rest of the world.

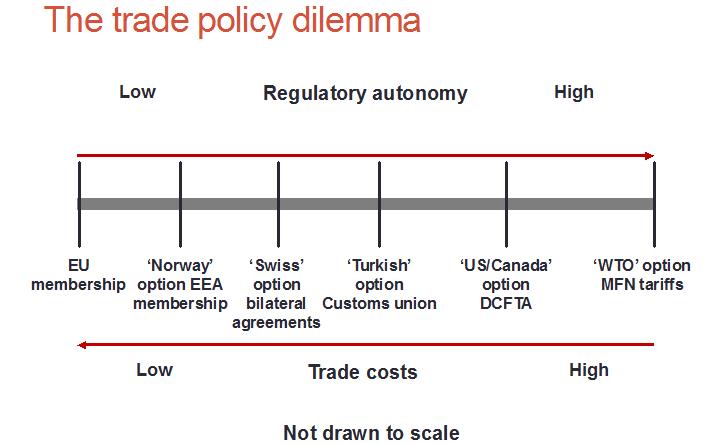

Considering first what he calls “the trade policy dilemma”, Matthews sets out a useful continuum of possible approaches (see below). If the UK were to pursue a different regulatory approach from the EU, then he suggests trade costs (tariffs + administration costs) would increase. Conversely in order to keep trade costs down, a Norway-style EEA membership approach covering agriculture would require the UK to completely, or largely, follow EU rules.

Trade costs matter to the UK agriculture industry and to consumers as they impact on food and farm gate prices. The EU applies a range of tariffs to agricultural products coming from outside countries. It has a number of preferential agreements which typically allow set quantities of agricultural product onto the EU market at preferential tariff rates (known as Tariff Rate Quotas, or TRQs). However, in the absence of a specific bilateral trade agreement, the default position for members of the World Trade Organisation is to apply what are known as the Most Favoured Nation (MFN) tariff rates.

In 2014 the EU’s average applied tariff for all agricultural products was 12.2%, but this masks a range of tariffs applied to different products. The EU’s dairy producers in particular benefits from average applied tariffs of 42.1%, whilst the EU’s tariff for meat and meat products sits at 17.7%.

Under WTO rules, the UK government could not increase existing tariffs, but it may choose to reduce them. Whether the UK would seek to reduce consumer costs by reducing tariffs, or to support elements of the industry by granting them tariff protection is yet to be seen.

Prof Matthews’ expectation is that the UK would seek to negotiate a future EU27-UK agri-food trade agreement to keep trade flows duty-free, but this would require a specific trade agreement and time will be of the essence to avoid disruption of supply chains. The UK would also have to renegotiate the web of EU’s free trade agreements and the shares of TRQs that the EU has negotiated.

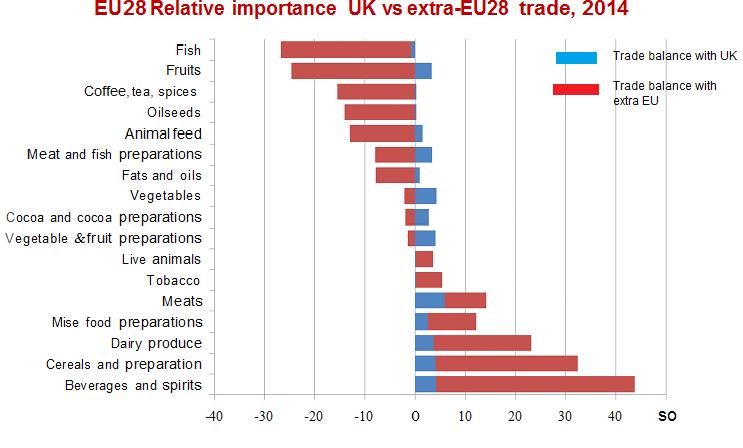

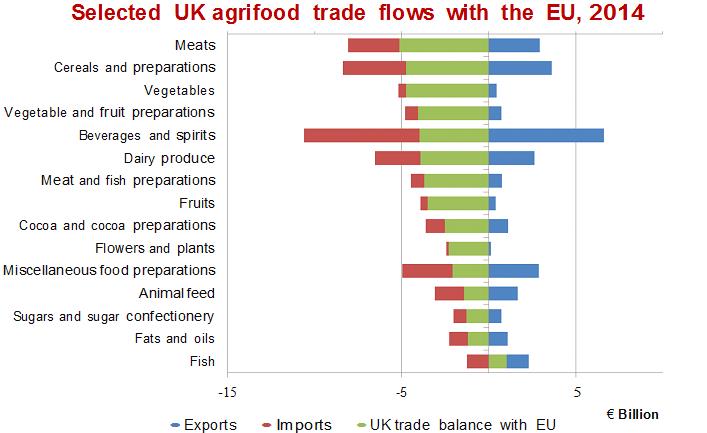

Across all traded agriculture commodities, with the exception of fish, the UK is a net importer from the EU.

Matthews argues that whilst imports dominate the statistics, UK exports to the EU are significant and rather than consider net trade flows, one should consider the gross trade situation (see graphic two below). For many sectors access to the EU market is critical; not withstanding that the UK market is important to the EU exporters, the fact that the EU’s trade balance with the rest of the world dwarfs the EU-UK balance (graphic three) suggests that the EU is a much more important partner for the UK than the UK is to the EU.

More...

- EU referendum: NFU urges PM to answer key questions

- BREXIT report predicts uncertainty and anxiety for farmers

- Our EU Referendum pages

- Read the Worshipful Company of Farmers' ‘Agricultural Implications of BREXIT’ here

- Read our report: UK Farming's Relationship with the EU

- EU debate: Raymond stresses need to guarantee competitiveness

- Blog: Nine questions that need answers in the EU In-Out debate

UK food prices post BREXIT

Prof Matthews considers the evidence base on food prices post BREXIT.

He finds that although the EU maintains high agri-tariffs in relation to other major agri-food exporting nations, EU farm prices are now close to world market levels. The UK imports two-and-a-half times more from the EU than it does from the rest of the world and any additional trade costs (as outlined above) would add pressure on consumer prices.

Even if the UK were to cut its MFN imports tariffs, the effects could be cancelled out by increased transaction costs on trade to audit rules of origin, administer the sanitary and phytosanitary checks and to ensure compliance with other requirements at the border. He estimates, based on literature reviews of other studies undertaken, that such transaction costs are the equivalent to tariffs on exports and imports of at least 5%.

The overall impact on food prices of a BREXIT could therefore be negligible. He notes that reduced tariffs in a sector such as sugar could quickly be replaced by other levies such as an obesity tax.

Macroeconomic channels

Farmers are significantly influenced by some key macroeconomic factors; exchange rates, interest rates, budget transfers and fiscal resources and migration policy and labour availability. Prof Matthews argues that there is a high consensus amongst economists that BREXIT would lead to greater uncertainty, although there is less consensus regarding impacts on growth rates and foreign investment flows. Greater uncertainty, he argues will lead to lower exchange rates (which would be positive for farming) but higher interest rates (concerning given record borrowing rates to UK farmers.)

Regulatory standards

Finally Prof Matthews considers the future of UK regulation post BREXIT. He ponders whether UK standards would be different/lower post BREXIT? Regulatory standards such as the use of growth promotors, pathogen reduction treatments, GMOs and maximum residue levels all play an important part in facilitating cross-border supply chains. Could there be a danger that the “Great British” food brand becomes associated with lower standards in the future if there are different approaches post BREXIT?

- Alan Matthews is Professor Emeritus of European Agricultural Policy in the Department of Economics at Trinity College Dublin. He regularly blogs on EU, CAP and trade issues on the site http://capreform.eu/