There was little time for the newly-formed NFU Norfolk to find its feet before it faced its first major test.

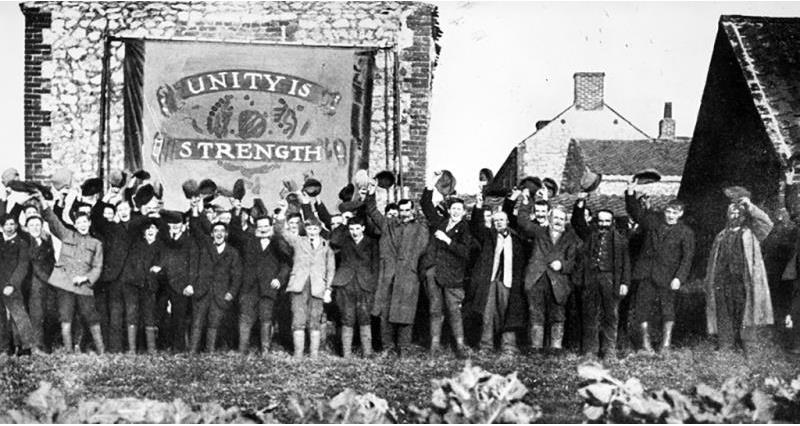

Thousands of farmworkers in Norfolk took part in the Great Strike in 1923, which was to cause bitter divisions and sour industrial relations for years.

An estimated 7,000 workers went on strike, although some estimates suggest that 10,000 or even 20,000 took part.

The seeds of conflict were sown in 1921, when the Government reneged on a four-year deal to support agriculture, the so-called Great Betrayal.

Wheat prices plunged, halving in value in just six months. With wages one of the biggest single costs, farmers were desperate and foot-and-mouth disease, drought and a poor 1922 harvest added to their problems.

In 1921, the wage rate was 44 shillings (s) and five pence (d), for a working week of about 50 hours.

After the Agricultural Wages Board was abolished, and farm support scrapped, the Government set up county conciliation committees with equal membership of employers and trades unions. However, as history was to show, neither side had faith in this political solution.

In September 1922, Norfolk’s conciliation committee recommended 25s per week. As prices fell again, the NFU’s eight members proposed more reductions. One of Norfolk NFU’s founders, George Mutimer, told Diss branch members in February 1923 that “the labourer must recognise that his interests were our interest”.

Instead, it sparked fury among the unions. With around one-third of Norfolk farmers now NFU members and prices continuing to fall, strike action was expected. There had been recent walk-outs in west Norfolk and around St Faith’s, Norwich.

On 9 March, Mr Mutimer advised a further wages cut, to 22/6d for the summer’s 54-hour week, and there would be no guarantee that work would be available.

Talks were held at the Bishop of Norwich’s Palace but without success. A delegation including George Edwards, of the National Union of Agricultural Workers, and Norfolk’s Henry Overman and Jim Wright met at Downing Street on 17 March.

The workers wanted the wages’ board back and farmers pressed for import tariffs, which would boost prices and make it possible to pay higher wages.

But the Prime Minister Bonar Law, who was to resign just two months later through ill health, refused to take action.

When notice of the wage reduction was posted on 16 March, battle lines were drawn. About 1,500 men in the Castle Acre, Massingham, Walsingham and Fakenham areas came out, and others around Aylsham and North Walsham stopped work.

The dispute became increasingly bitter and Norfolk’s Chief Constable was worried as large bands of up to 300 cycling pickets descended on farms and ‘persuaded’ men to come out. He even asked for 600 officers from across the country to help deal with incidents.

But, it was hard for the strikers, surviving on 6s a week, to maintain the strike and, when union funds began to be exhausted, a settlement seemed desirable.

Ramsay MacDonald, Labour’s leader, was asked to intervene. He had just settled a dispute in the builders’ trade. On 18 April, both sides met at the House of Commons and agreed on 6d an hour or 25s a week for 50 hours.

It ended the strike but it took almost 20 years for wages to return to 1919 levels, as the agricultural depression became even more severe.

Find out more about NFU Norfolk's first 100 years by clicking on the links below:

- NFU Norfolk - 100 years of growing

- A century of growing - read our souvenir publication here

- Farming in numbers, then and now

- NFU Norfolk - how it all began

- Finding a home for NFU Norfolk

- NFU spitfire flies high

- A voice for farming - politics, protest and persuasion

- Sowing the seeds of farm environment schemes

- Half a century of membership - meet farmer William Brigham

- Join in the NFU Norfolk centenary celebrations