Independent regulatory bodies around the world have looked at the available scientific evidence and concluded the glyphosate poses little or no risk to people when used correctly.

On March 15 2017, the Committee for Risk Assessment (RAC) of the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) completed an extensive review of all the available scientific evidence on glyphosate and concluded it should not be classified as a carcinogen or as a substance that causes genetic or reproductive effects. ECHA is a regulatory authority on the safety of chemicals and a key adviser to the European Commission on the risks of substances to human health.

Tim Bowmer, the committee’s chair, said: “RAC agreed with the German dossier submitter that glyphosate should not be classified as a carcinogen – that is, as a substance causing cancer. This conclusion was based both on the human evidence and the weight of the evidence of all the animal studies reviewed. In addition, RAC concluded that glyphosate does not warrant classification as a mutagen – that is, a substance causing genetic effects – or as a substance causing reproductive effects.”

He concluded: “The committee’s opinion was adopted by consensus – that is, with the full support of all the members and there were no minority positions.”

More on this topic...

- Our dedicated glyphosate pages on NFUonline

- Glyphosate - we need your support

- Inform the debate with our Glyphosate is Vital leaflet

- NFU welcomes ECHA decision reinforcing glyphosate's safety

- How Glyphosate Works for Us All - download our infographic here

ECHA’s conclusion reflected the conclusions of regulatory bodies around the world who had concluded glyphosate posed no human health risk when used correctly. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) carried out a review which concluded that glyphosate is unlikely to be carcinogenic and poses minimal risk to non-target plants and animals when used appropriately. This conclusion is consistent with the outcome of other regulatory evaluations of glyphosate around the world, in countries including the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Germany – all of which supported the conclusion that glyphosate posed no unacceptable risk when used correctly. This view was also upheld in a joint report from the World Health Organisation and the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the UN.

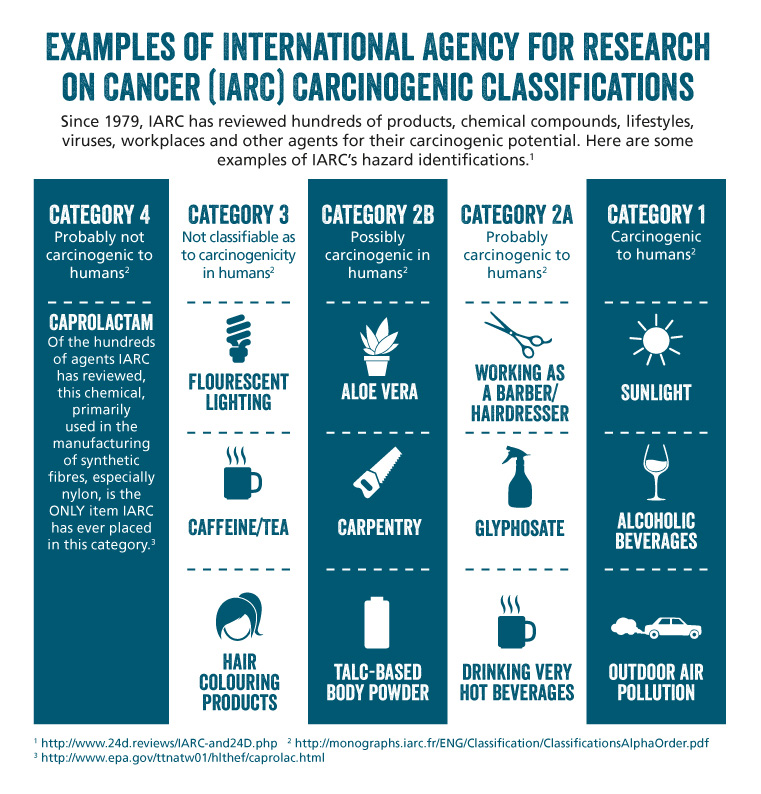

The only body that has concluded that glyphosate is cancer risk to humans is the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) which concluded glyphosate is “probably carcinogenic to humans”. While IARC is an agency of the World Health Organisation (WHO), the WHO itself has upheld the view the glyphosate is safe.

IARC seeks to identify cancer hazardsmeaning the potential for the exposure to cause cancer. But it does not indicate the level of risk associated with exposure, which can depend on a number of factors including the type and extent of exposure. IARC has said its classification programme may identify cancer hazards even when risks are very low with known patterns of use or exposure.

IARC’s identification of hazard is only the first step of the human health risk assessment process. Only when the hazard is considered together with the risk (exposure in everyday situations) can the human health risk, if there is one, be determined. These health risk assessments are carried out by organisations EFSA, the WHO and national regulatory bodies. And that health risk assessment, based on the best available scientific evidence, is currently undisputed – glyphosate poses no carcinogenic risk if used properly and for its intended purpose.

It is worth noting that pesticides are among the most tightly regulated chemicals in the world. Research released in April 2016 showed that, on average, to meet the requirements of that regulation and bring a new product to market it takes 11 years and costs around $286 million (around £233 million). This is an exhaustive and thorough process that affords very high levels of protection to both human health and the environment.